|

| Swarovski and the New York City Ballet For New York City Ballet’s collaboration with Swarovski on costumes for George Balanchine’s Symphony in C, Marc Happel, the company’s director of costumes, stayed true to the original color palette while adding “a new kind of sparkle, a new kind of flash.” On opening night at the New York City Ballet gala on May 10, male dancers will wear black velvet tunics embellished with jet crystals, and the women, white tutus and a top layer detailed with a spray of stones. The sparkle will be head to toe: with jeweled crowns and fanned head dresses, as well as earrings by the former NYCB corps de ballet dancer turned jewelry designer, Jamie Wolf. Photo: Nick Bentgen |

The Ballet's history:

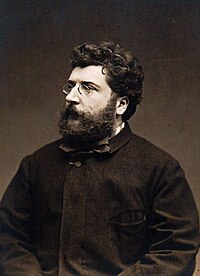

Symphony in C, originally titled Le Palais de Cristal or Crystal Palace, is a ballet made by New York City Ballet co-founder and balletmaster George Balanchine to Bizet's Symphony in C (1855), which Bizet wrote at the age of 17 while studying with Charles Gounod at the Paris Conservatory.

|

| George Balanchine |

The manuscript was lost for decades, and was published only after it was discovered in the Conservatory’s library in 1933. Balanchine first learned of the long-vanished score from Stravinsky. He required only two weeks to choreograph it as Le Palais de Cristal for the Paris Opera Ballet. When he revived the work the following year for the first performance of New York City Ballet, he simplified the sets and costumes and changed the title.

The premiere was on Monday, July 28th, 1947, in the Théâtre National de l'Opéra with the Paris Opéra Ballet where Balanchine was serving as a guest ballet master at the time. According to City Ballet docents the four movements were originally associated with and designed using the colors four gemstones, three of which Balanchine subsequently retained for the three movements of his 1967 ballet Jewels: Emeralds, Rubies and Diamonds. Even before the ballet was renamed Symphony in C, he had eliminated the color scheme and changed to the white costumes still used.

The NYCB premiere took place as the final piece on the first performance, October 11, 1948, of the newly renamed City Ballet at the City Center of Music and Drama with costumes by Karinska and lighting by Mark Stanley. Jerome Robbins was in the audience at that performance and is quoted as saying that he immediately wrote to Balanchine asking to be hired in any capacity.

|

| George Balanchine and Barbara Karinska fitting Suzanne Farrell for Don Quixote, 1965. Scanned from Costumes by Karinska by Toni Bentley. |

| Katia Carranza & Renato Penteado in Balanchine's "Symphony in C |

|

| The NYCB dances the finale of Balanchine's SYMPHONY IN C. kylefromanphotography.com |

Over 105,000 hotfix crystals, sew-on stones and fancy stones in crystal, midnight blue, black diamond and jet, were used on the women’s tutus and men’s costumes. The variety of stones and crystals create a dramatic and intricate design on each costume, which glitter beautifully as ballerinas jete and pirouette across the stage.

Former NYCB corps de ballet member Jamie Wolf, now a well-known jewelry designer, created original earrings, also incorporating Swarovski elements, which will be worn in the production. The earrings will be available for sale on Jamie Wolf’s website, with a portion of proceeds benefiting NYCB’s “Turn Out” fundraising program.

Tickets for the NYCB Spring Gala:

The ballet's structure:

As with many Balanchine ballets, Symphony in C has no underlying story. It is a representation of the music by means of movement. Every single movement of Bizet’s symphony corresponds to a different choreographic scheme, with basic motifs and patterns for the corps de ballet; each led by a principal ballerina and a danseur. As such, the ballet has four movements, each featuring a different ballerina, danseur, and corps de ballet. The entire cast of 48 dancers from all four movements gather for the rousing finale.

The Adagio (aka “Bend & Snap“): Here the music is more lyrical and sentimental, so in several portions the mini-corps frames the principal couple (think Swan Lake Act II Pas de Deux) while they dance a Pas de Deux filled with lifts, balances and extensions; there are plenty of supported penchés, including the “nosedive into knee” made famous by Suzanne Farrell. As the music picks up mid-movement, the ballerina starts her variation. The section ends with the corps framing her again while she lets herself fall into her partner’s arms.

Allegro Vivace (aka “Might as Well Jump”): The music becomes energetic and full of momentum. This section opens with the mini-corps - six girls and two soloist couples - grand jeté-ing across the stage. The main couple enters in a manège of grand jetés interlaced with single saut-de-basques and temps levée. They get to the middle of a triangular formation; everyone relevé-ing non-stop. The main couple fly off the wings, returning after soloist couples and corps have engaged in yet more jumping. Repeat. Leads enter for the last time, displaying bravura jumps, pirouettes and quick-footed steps, all the way back to front and then in diagonal lines. This section concludes with the corps kneeling and looking gracefully towards the audience while the ballerina is held in arabesque by her partner.

Allegro Vivace (aka “Let’s Do What They Just Did”): In this final movement all principal couples join the fourth couple for an over-the-top display of technical prowess. It opens with the fourth ballerina going through a sequence of turns (many pirouettes & fouett ées), small jumps and changing poses, the corps moving around her. Her partner and two male soloists enter in blazing grand jetés and it all builds up from there.

After the briefest of pauses as the fourth couple finishes their variation, all leads, soloists and corps de ballet join in. The ballet ends with all 48 dancers assemblé-ing in unison into a rousing finale; all principal ballerinas fall into their partners’ arms while soloist ballerinas are lifted in the background.

Georges Bizet (1858-1875) is said to have composed his symphony while he was a 17-year old student at the Paris Conservatory as a class assignment. The score was discovered in the Conservatory’s library in 1933 (80 years thereafter), having never been mentioned by the composer in his letters and unknown to his early biographers. One of the theories behind it was that the piece had too many similarities to Symphony No. 1 in D (1855) composed by Bizet’s own teacher Gounod. Nevertheless, Symphony in C showed how gifted Bizet was as a melodist and orchestrator.

|

| Georges Bizet |

II. Adagio 9:37

III. Allegro Vivace 5:55

IV. Allegro Vivace 8:43

Le Palais de Cristal

- Costumes & Designs: Léonor Fini

- Premiere: 7 July, 1947 by the Paris Opera Ballet. Thêatre National de L’Opéra.

- Cast: Lycette Darsonval, Alexandre Kalioujny (1st Mov); Roger Ritz, Tamara Toumanova (2nd Mov); Michel Renaul, Micheline Bardin (3rd Mov) and Madeleine Lafon, Max Bozzoni (4th Mov).

Symphony in C

- Costumes: Barbara Karinska

- Designs: Mark Stanley

- Premiere: 11 October, 1948 by the New York City Ballet at NY City Center.

- Cast: Maria Tallchief, Nicholas Magallanes (1st Mov); Tanaquil LeClercq, Francisco Moncion (2nd Mov), Beatrice Tompkins, Herbert Bliss (3rd Mov), Elise Reiman, John Taras (4th Mov).

Sources:

1. DiamondNews (http://s.tt/1bgYd)

2. Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Symphony_in_C_(ballet)

3. The George Balanchine Trust http://balanchine.com/symphony-in-c/

4. The Ballet bag http://www.theballetbag.com/2010/02/05/symphony-in-c/

5. Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georges_Bizet

6. The New York City Ballet http://www.nycballet.com/nycb/home/

Wonderful post! We are linking to this great post on our site.

ReplyDeleteKeep up the good writing.

Feel free to surf my blog post ... Posted by My Industrial Injury Claims.com